Wolf has been preparing for this heat and this moment for a decade, more like three decades. Inside his garage is what he calls a small "Hurricane on wheels,” the most high-tech firefighting equipment yet invented. His timing for introducing it comes at a critical moment.

Since 2020, Colorado has experienced three of its largest and most destructive wildfires: the Cameron Peak fire in Roosevelt National Forest, the East Troublesome fire in Arapaho National Forest, and Boulder County’s Marshall fire. Nationally and internationally, the story is the same. Canada is burning, New York City was recently blanketed in smoke, and Maui is still smoldering after the deadliest fire of the last century, killing around 100 people. The globe is getting hotter and wildfires are increasing across the planet, consuming more lives, trees and structures and putting more CO2 into the atmosphere. But Wolf has a vision and a plan.

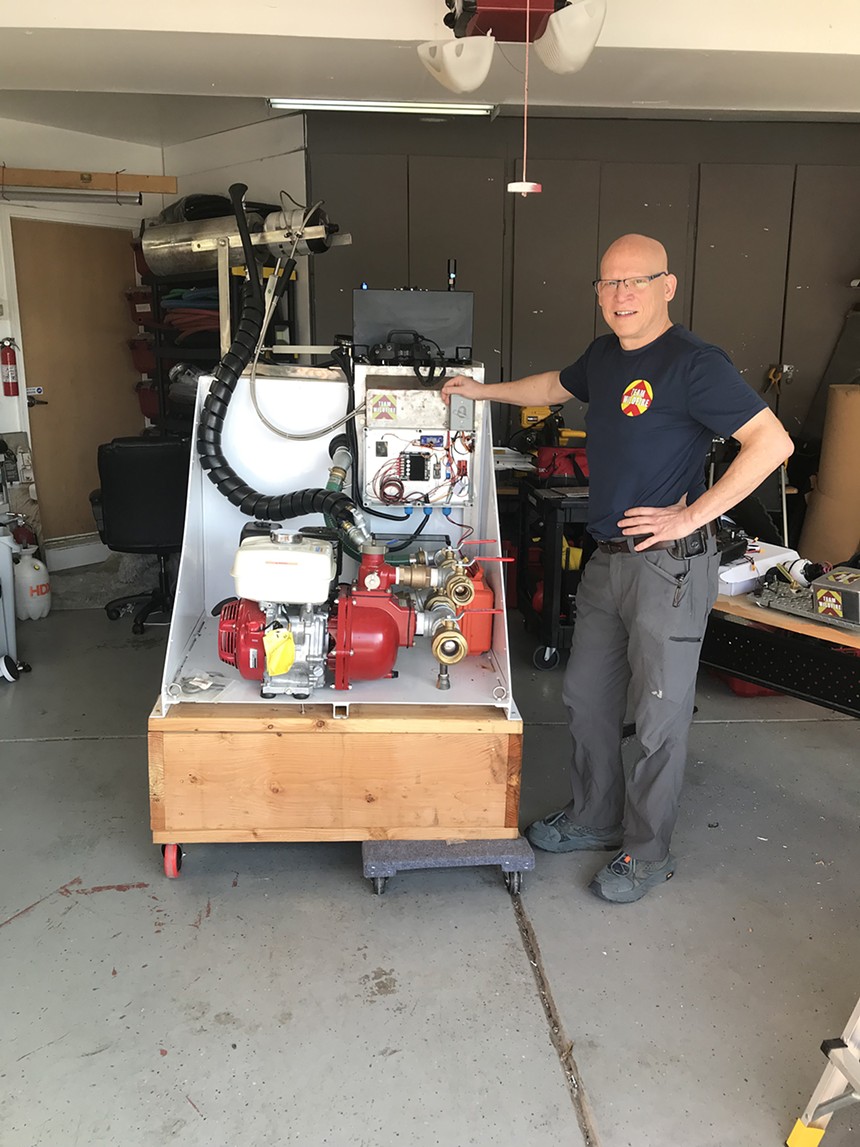

“Weather, particularly the wind, rules fires,” he says, walking into his garage and putting his hand on a Hurricane prototype known as CloudBurst, a self-contained fire-suppression system that can be dropped into any pickup truck and deployed immediately. “You own the wind, you own the fire.”

A four-foot-by-six-foot machine on a mobile platform, CloudBurst has a Honda pump in the body and a small jet engine on top; other parts came from Home Depot or Amazon. The CloudBurst costs under $100,000, weighs 400 pounds, holds 200 gallons of water, and is run by a hand-held remote control. Pressing buttons that make the equipment move, Wolf looks like a man flying a model airplane or manipulating a robot.

“If weather rules the fire,” he says, starting up the CloudBurst, “we have to rule the weather.”

But how?

Born in 1963, Wolf spent his early years in Switzerland before moving to New York City. His father, Burt Wolf, became a PBS host for food and travel programs, exposing his son to the entertainment business from a young age. The boy loved science, but a fourth-grade teacher told him that he’d never amount to anything in that field because the margins on his science papers were skewed. (Forty years later, he toasted her posthumously when he keynoted the National Science Teachers Association conference — and he’s a two-time winner of the Science Presenter of the Year award, an honor given by Time Warner.)

Despite his disdain for how science was taught in school, Wolf was fascinated by the television show Emergency and its use of stunts and special effects. Like countless others, he watched TV programs and movies — always asking himself, “How do they do that?” — and was determined to learn more. At Columbia University, he earned a degree in writing and literature, studying Shakespeare by day and attending paramedic classes at night. He bought an ambulance and started a business called Cinemedics, standing by on movie and TV sets, poised to help those who got injured. The more he observed the action, the more he was convinced of one thing.

“We needed a lot more science and a lot less cowboy-ism," he says. "A stunt is a physics demonstration with a human payload. Using more science when planning stunts could reduce injuries on sets.”

He needed a mentor in the filmmaking business and heard about special effects guru Gary Zeller, an expert in the science behind movies who'd invented Zel Gel, the gooey substance applied to stunt performers so they don’t get burned when set on fire. (Zeller won an Oscar for this in 1986.) Wolf called him up and offered to carry his bags, make his coffee or sweep his shop for no pay.

Two weeks later, Zeller hired him. They launched Z Team Productions and began working together on movies. In 1991, when Tom Cruise’s people asked Zeller to come to Memphis and assist on The Firm, he said he’d moved on to environmental issues and handed Wolf the phone. The young man headed to Memphis, taking Cruise to a shooting range and showing him how to handle guns safely on the set.

During filming, director Sydney Pollack asked Wolf to manage a small fire they’d been using for a scene. “You don’t have to put it out,” Pollack said, “but it can’t stay here.”

Wolf found a leaf blower and “moved” the fire thirty feet away from the action. It was the first time he realized that with the right amount of wind, you could control, and even relocate, fire. It may have also been the first time that his future motto — “If it’s impossible, count me in” – entered his mind.

The Firm was based on a book by John Grisham, who had other stories to be filmed in Memphis. While creating special effects, Wolf worked with numerous A-listers, including Tom Hanks, Samuel L. Jackson and Robert De Niro. He spent eight years in Memphis, honing his skills as a stunt/special effects/pyrotechnics/explosives coordinator and opening a pistol range on a property once owned by Elvis Presley. He loved the job, but science tugged at him.

In 2000, Wolf relocated to Austin, Texas. Two things were now simultaneously unfolding within and around him: He was learning more and more about the scientific aspects of filmmaking — how to crash cars, shoot people and blow things up without harm — as the earth was getting hotter and more vulnerable to wildfires. He’d never stopped thinking about the leaf-blowing incident on the set of The Firm and wondered if something more could be done with that idea. But he was too busy on other fronts (scuba diving, public speaking, working as a trial consultant, fathering three sons) to develop the concept.“Weather, particularly the wind, rules fires. You own the wind, you own the fire.”

tweet this

During downtimes in the movie business, he hosted several shows for cable networks, including Houdini’s Last Secrets, What Destroyed the Hindenburg? and Ancient Impossible, and opened an “edu-tainment” park called Stunt Ranch. He brought in corporate execs for team-building sessions but wanted to do something for children. What he’d learned as a boy sitting in science classes was how not to teach science. He invited youngsters to the ranch to experience firsthand the science of stunts — by making things physical.

“If you want to teach kids about the physics of falling,” he says, “have them fall through space. Let them experience science inside their bodies.”

He created a live school assembly called “Science in the Movies,” revealing the STEM content behind movie stunts and special effects, and performed more than 5,000 shows. Viewing his presentation, kids would holler and squeal when he lit a 2,000-degree-fire in his hand (covered with Zel Gel insulation) and hoisted school principals atop stages with pulleys. He also did volunteer firefighting, which again made him think about The Firm. He and the other firefighters were sent into the field with picks, axes and shovels. He was startled by the primitive equipment.

“Our tools were medieval,” he says, “but I shouldn’t have been surprised. Even firefighters describe their industry as ‘200 years of tradition unimpeded by progress.’”

What, he asked the firefighters, is your strategy for dealing with burning forests?

“They told me that they were hoping for it to rain or for the wind to change direction,” Wolf recalls.

He asked what it would actually take to push back and knock down large fires.

“A hurricane,” they joked.

That got him thinking even more.

Wolf started noodling with the idea of building a mega leaf blower, using jet engines outfitted with mist injection chambers. He called Gary Zeller and asked if he thought the idea had merit. Zeller was so enthusiastic that he offered to help Wolf write a patent for the machine. But before they could begin, Zeller died of pneumonia, and the plan stalled.

After two decades in Austin, Wolf’s life was evolving again. Climate change was making the city “horrifically hot,” and in 2020 the pandemic struck, shutting down the ranch. He began looking for a cooler climate where he could engage with new people and challenges, and not just any town would do. He was searching for the kind of folks who embrace innovation and high-tech solutions to complex problems. He liked being around visionary people who enjoyed tackling “unsolvable” problems. Boulder fit the bill.

Settling into Colorado, Wolf finally had time — with COVID’s help — to address some fundamental questions. Movie directors were always asking their technical crews to do the impossible — and getting the results they wanted. Why should a movie director have access to weather on demand when a fire chief doesn’t? Why couldn’t Wolf take the notion of “I saw it at the movies!” to another level? The level of reality.

Wolf has another favorite saying: “Every situation is an opportunity.” COVID was definitely a situation, and as it took hold across the country, he remembered something that Zeller had told him decades earlier: “Creativity flourishes absent of distraction.”

Sitting above Boulder, where he'd watched the December 2021 Marshall fire — which had killed two people, destroyed over 1,000 homes and caused $2 billion in damages — he drew up a schematic for the Hurricane.

“Look at all the technology we turned to that failed during the Marshall fire,” he says. “The hoses burned up. The trucks couldn’t keep pace with the fire. The wind took over. Our tech could have helped.”

Working 80 to 100 hours a week, he learned how to write patents and then wrote four of them, including one for CloudBurst, which took more than a year. He reached out to engineers and creative thinkers in physics, chemistry, meteorology and other fields. He had a lot of contacts (11,000 of them on LinkedIn alone) and did a lot of Zooming. As he got to know Boulder, he began meeting the kind of people he was looking for.

One was Jamie Brandess, who ran Boulder’s Small Business Development Center.

“I started working with Steve during the very early stages of Team Wildfire,” she says, “and I was very excited about his idea and his innovation. I provided some initial insights into how to get the business started and connected him to resources. Wildfires are close to home for me because I live in Evergreen, where the wildfire risk is extremely high. I’m constantly doing what I can to mitigate the area around my home against fire. When each wildfire started, I always wished Steve’s invention was available in the market to assist during those disasters. I truly believed his innovations would save lives, put firefighters at much less risk and reduce the loss of structures to wildfires. He knows how to dream big and get things done.”

Wolf got to know Andy Amalfitano, a business executive and the volunteer leader of an emergency search-fire-rescue response team in Boulder. He’d been directly involved in managing functions on some of the major forest fires in Boulder County.

“Steve and I met at the Boulder Emergency Squad, which he’d joined as a rescue candidate,” Amalfitano recalls. “When I heard about his vision of developing autonomous firefighting machines, I was intrigued. My experience with managing small and large businesses, as well as a few startups, could be of value. I immediately realized that we needed an expert with experience in wildfire management. I turned to Dan Eamon, who has extensive experience actually fighting wildfires.”

Eamon, the emergency management director for Longmont’s Public Safety Department, had guided the LPSD’s response to natural disasters. “The Hurricane,” Eamon says, “has the potential to be a transformative technology in combating wildfires. The ability to deliver cooling mist and retardant over long distances in a ground-based platform could be game-changing. We can all see the differences in fire behavior in the past few years, and something has to be done to bring new suppressive technology to the fire ground. Excellent work is being done in the detection and prevention space, but little is being done to help put fires out. If we can bring a vehicle that can deliver the same amount of retardant as a large air tanker but can operate on a continuous basis, it could give incident commanders radically new options.”

As Wolf refined his concepts, the fires kept coming, driven by climbing temperatures, droughts and stronger winds. FEMA reported that in 2022, the U.S. saw 66,255 wildfires that burned 7,543,403 acres. In Colorado last year, 835 wildfires burned 45,732 acres.

“These fires should be a really significant red flag,” LeRoy Westerling, a climate and wildfire scientist at the University of California, Merced, recently told the Washington Post. "All over the world, this is happening right now…a warning sign that something’s happened that we need to take into account.”

Wolf’s home has been visited by coyotes, cougars and mountain lions. He once found a bear rummaging in his garage. At the foot of the steps leading up to the main floor, where many people might have plants or statues, are two large fire extinguishers, part of the thirty prominently featured at his home. The living room’s windows provided Wolf a broad view of the Marshall fire, driven across the Front Range by howling winds. A small stairway leads to Wolf’s office, set up for the interviews he does with News Nation, CNN and other media outlets. Sound baffles on the walls evoke a recording studio, and a ring light illuminates his face when on camera.

At Stunt Ranch, he once trained CNN anchors in how to handle firearms. In October 2021, when the story broke in Bonanza City, New Mexico, about the fatal shooting during the filming of the Alec Baldwin movie Rust, CNN called Wolf for commentary. On his desk is the same model as the deadly weapon: a black, single-action Colt 45. He picks up the unloaded gun, spins the chamber, cocks the pistol, and delicately puts his finger on the trigger, showing how very little pressure could fire the gun. Plaintiffs in the case hired him as an expert witness for the trial this December.

Bald, trim and bespectacled, Wolf could easily be cast as a scientific genius in a motion picture. He does a killer German accent. He wears a dark-blue shirt with “Team Wildfire” across the front and “Wolf” on the back. He has on cargo pants full of…cargo. If his garage resembles a hardware store, his office is a techie’s paradise, with gadgets everywhere. As he speaks, he seamlessly bounces from science to fundraising to real estate to media to tech to public relations to teaching science to whatever comes next. His focus is intense, and when he pauses after delivering a monologue on one subject, it takes him about a second to reboot. In some ways, he brings to mind a computer — wired for constant input and output.

On his computer screen, he calls up a picture of a young girl wearing her dead father’s fireman’s hat. Since 1992, 522 firefighters have been killed in the line of duty.

“No firefighter should be put in a position to die while doing their job,” he says, wiping at his cheek and turning away from the girl’s image. “Every place now has the potential to be a Maui or a Marshall fire, so we have to do better and use technology that can go where firefighters shouldn’t have to.”

Annually, U.S. wildfires cause $350 billion in losses and release billions of tons of CO2 into the atmosphere. Reducing them by 10 percent would decrease it by emissions equivalent to that of 174 million cars.

As fires have recently intensified, so has controversy about managing America’s natural resources. Many believe that the fire suppression work of the U.S. Forest Service and Bureau of Land Management during the past century has led to overgrown, unhealthy forests that threaten wildlands and communities. In Colorado and far beyond, a bitter dispute exists between ecologists who think the forests should be left alone and conservationists or entrepreneurs who feel they should be cleared of dying or dead wood. On one side are those like Josh Schlossberg of Longmont, a Colorado steering committee member of the Eco-Integrity Alliance.

“While wildfire has been a natural and essential process in our western forests for millennia,” Schlossberg says, "84 percent in the U.S. nowadays are started by humans, including nearly all of Colorado’s largest. … Our government is wasting billions of our tax dollars logging public lands, which studies in Colorado show does nothing to slow large wildfires and can instead make them burn hotter and spread flames faster, punching thousands of miles of new roads into the heart of the forest while leaving communities to fend for themselves. …

“The entire premise of ‘overgrown’ forests that somehow ‘benefit’ from logging or in any way ‘protect’ communities from wildfire has been challenged by independent science, while demonstrating that agency-funded studies have deliberately distorted their findings to support logging," he adds.

On the other side are those like James Gaspard, who runs the Berthoud-based company Biochar Now. “The opposition wants to leave everything alone,” Gaspard says. “We’re saying take away the excess dead wood and restore the natural forest. All the rotting trees are putting more CO2 into the air. The reality is that we have a sick forest, and the dying and diseased wood needs to be removed to make it healthy.”

Wolf comes down on that second side of the argument.

“Taking out unhealthy trees increases the distance between trees and makes it harder for fires to spread," he says. "Harvesting trees and turning them into lumber guarantees that the carbon they have sequestered is retained, as opposed to the risk of having them burn and release all their carbon back into the atmosphere. Smart money knows when to hold on to your winnings.”

July 2023 was the hottest month on record — the same month that Canada suffered a record wildfire season. Firefighting, Wolf believes, is not a problem best left up to government.

“Private industry,” he says, “is leading innovation on the wildfire front.” But he struggles with some of those innovations.

“We’ve spent millions of dollars on satellites, cameras and sensors, and they have their purpose in locating fires, but here’s the question: How many satellites does it take to put out a fire? How many sensors? No amount. Because data doesn’t douse fires," he notes.

Echoing the sentiments he teaches children about physics, he adds, “Fires are a physical phenomenon in the real world. When you have a physical problem, you need a physical, not a virtual, solution. That’s where the Hurricane comes in.”

After creating the specs for his proof of concept for CloudBurst, Wolf began looking for larger used jet engines, which can be purchased for around $30,000 from a jet engine graveyard in Arizona. “Just because an old engine is no longer allowed to take to the skies doesn’t mean it can’t put out fires," he says.

He reached out to Tim Draper, a renowned venture capital investor, who put together $500,000 to fund the Storm Cloud and the CloudBurst prototype. A fire needs four components to keep burning: heat, oxygen, fuel and chemical reactions. The Hurricane technology is designed to get rid of them all. Affixed to the engine is a cylindrical “mist injection chamber” containing 180 tiny nozzles that infuse the jet exhaust with powerful fire suppressants. On contact with extreme heat, the water-based suppressant forms steam, which displaces oxygen. Evaporative cooling reduces heat, and the forceful exhaust blows away fuels (sticks, brush, fallen leaves and undergrowth). Other chemistries halt the reactions.

The single-engine CloudBurst can be placed on off-road vehicles or in pickup beds, giving it far more flexibility than a fire truck. It can navigate between houses in neighborhoods and tight alleys or go deep into the woods to attack fires that conventional equipment, and human beings, often can’t reach. It’s designed to save lives, and consumes a fraction of the water employed by conventional tools to suppress the same amount of fire.

The top wind speed of the Maui fire was around 80 mph. The full-size Hurricane will use several large jet engines mounted on logging vehicles and can create 250 mph gales strong enough to blow back a fire and shift its direction.

“An airplane,” Wolf says, “can drop retardant on a fire, but then has to fly off to reload, often returning to an entirely new set of conditions, and they can only fly safely during daylight hours, weather permitting. We can attack fire round the clock, in any conditions, as long as we have water and diesel. Firefighters are American heroes, but they’re victims of a lack of good technology.”

Wolf has one other tool at his disposal.

“We’ll use Artificial Intelligence to play chess with the fire,” he says. “Think Wildfire GPT. AI can intake tons of real-time data from sensors on our trucks. It can make predictions about fire movement, but that’s not new. The trick is continuously formulating the perfect suppression plan, based on what collection of firefighting assets you have available and what you’re working to protect.”

He was starting to think big.

“Steve Jobs was once asked how he could possibly compete with the likes of AT&T and Motorola," Wolf notes. "He said that he didn’t need to compete with them, he just needed to invent something that made them obsolete.”

In 2022, Team Wildfire was launched and business leader Andy Amalfitano joined Wolf's efforts. Dan Eamon quit as Longmont’s emergency management director to become part of the startup, and Jamie Brandess was being considered for a position with the company. Needing more funding, Wolf applied to Techstars, a business accelerator program that connects entrepreneurs, investors, corporations and city governments. After providing him with intensive business training, it invested $120,000 and has committed another $150,000. He approached Santa Fe’s Cottonwood Technology Fund, which committed to lead Team Wildfire’s next funding round with $2 million. He’s in talks with the Venture Fund Division of Denver Angels and MUUS Climate Partners.

In the summer of 2022, with the CloudBurst prototype built, Wolf and his team took it to Boulder’s Fire Training Center for a demo (online videos show what it can do).

“If we don’t get this kind of technology into the field fast, we have no chance against the fires coming our way," said Greg Schwab, chief of the Boulder Rural Fire Department, following the demonstration.

Then came the fire in Maui. As Wolf viewed the devastation on television, he was certain that a fleet of Hurricanes would have made a significant difference.

“Winds drove those fires,” he says, “so the solution is twofold: Push back against adverse winds with stronger winds, and use the jet engines to quickly lay down a wide barrier of chemical retardant in front of the fire’s leading edge. Unmanned vehicles can directly hit fires from the front. We could have covered buildings and wooden houses in town. Think of our tech as a nuclear-powered spray can on wheels. Or a fire extinguisher times 10,000. In Maui, they ran out of fresh water to fight the fires. We could have used seawater and never run out. We can protect people, property and the planet.”

In late August, a former National Park Service Hotshot firefighter and a representative of the U.S. Department of Energy visited Wolf’s home to check out his technology. The DOE rep told him that his Hurricane could help minimize fires ignited by electric transmission lines. (Maui County officials have blamed the fires on the state’s largest electric utility, claiming in a lawsuit that “intentional and malicious” mismanagement of power lines allowed flames to spark. Following the Marshall fire, seven lawsuits were combined into one big legal action against Xcel Energy.)

"Given that utility companies have been implicated in many of the costliest and deadliest fires," Wolf says, "they should be leading the charge to investing in technology that can make our electrical grids safer."

Gregory Vigneaux, the ex-Hotshot who examined Wolf's tech, has fought fires in more than ten states, going into remote and rugged areas to build “fireline” — a break in fuel made by cutting, scraping or digging.

“What Team Wildfire is creating,” he says, “has the potential to support, if not augment, how wildfires are fought. Being able to control the weather along the fireline may increase firefighter safety by securing the burning edge, behind or in front of firefighters. As a former Hotshot, I have a close connection with operations and can greatly appreciate what Team Wildfire is doing.”

After getting the next round of funding, Wolf plans to fly to Canada, where logging equipment manufacturer Tigercat has its headquarters in Brantford, Ontario. The full-scale, three-engine Hurricanes can be based on this machinery for mountain fires or used on Ardco-based trucks for off-road conditions. Then he’ll go to California to show the state with the most annual wildfires what his technology can do.

“They’ll start prescribed fires,” he says, “and we’ll turn the Hurricane loose on them.”

Wolf’s goal is to have Team Wildfire’s fleets standing by for rapid deployment wherever fires may start, anywhere in the world: Canada, Australia, Greece, Portugal, Italy…. In addition to putting out fires, he hopes to inspire others who harbor creative ideas to tackle challenges they’ve been told were impossible.

“In 1899,” he says, “the head of the U.S. Patent Office is — falsely — purported to have said they could shut down because everything had been invented. Clearly not. My generation has created very serious problems for the planet. Before we die, we should empower the next generation to solve some of these problems. If we’ve lit the world on fire, the least we can do is leave our kids the tools to blow it out.”